The 30 best countries, cities and regions to visit in 2025

May 15, 2018 • 16 min read

Begin your Mexican adventure in the winelands of Valle de Guadalupe, before venturing into cowboy country. Next, head to Bahía de los Ángeles to witness 'the world’s aquarium,' then drive on to explore colonial towns. Finally, take to the azure waters of La Paz, in the south of the peninsula.

This article appeared in the Summer 2018 issue of Lonely Planet magazine's U.S. edition.

Eat, drink and be merry amid the rolling hills of Baja California’s wine country.

As the sun sets behind towering pine trees, casting long shadows across the Mogor-Badan vineyard, Paulina Deckman is reminiscing about the first time she came here to eat. It was six years ago, and dinner was so good she married the chef. Drew, her Michelin-starred now-husband, had just opened Deckman’s en el Mogor as an open-air venue to showcase the best of the ranch’s fresh meat, fruit and vegetables alongside the plentiful seafood from the nearby port of Ensenada. 'For my husband and me, this is the Disneyland of the ingredient,' Deckman says. 'We serve in our restaurant the bounty of the Baja.'

Baja California’s Valle de Guadalupe is a special place for food and wine. It’s cooled by the Pacific Ocean, with a microclimate similar to that of the Mediterranean. It’s a climate that makes it easy to grow things. The weather is temperate and the hills are green. Squint and you might think you’re in Tuscany. Knock back too much local wine and you might think you’ve woken up in Napa Valley.

Then there’s the seafood. Every morning in Ensenada, oysters, shrimp, marlin, crab, tuna and more are piled high onto the stalls at the Mercado de Mariscos. Serving up a plate of pearly white scallops, Deckman notes: 'These are a signature from Baja California. They’re so fresh they would have been in the water this morning.'

Deckman’s takes the farm-to-table philosophy one step further. Rather than bringing the farm to its diners’ plates, it brings its diners to the farm. Everyone eats outdoors, beneath the shade of the pine trees, with the scent of the kitchen’s wood-fired stoves in the air. 'Sometimes people complain about the flies, but we are on the farm and we have to understand the context,' says Deckman, as she deftly shoos one away from a tray of oysters. 'We may serve fancy food, but this is not a fancy place.'

The Deckmans are vocal supporters of the slow food movement, that necessary corrective to an obsession with fast-food restaurants. 'Here, our food chains are as short as possible,' she says. 'We try to be a zero-kilometer restaurant. Everything the ranch produces, we serve.'

Other restaurants in the valley are following their lead. Nearby TrasLomita also has its own farmyard and vegetable patch growing ingredients at their sister vineyard, Finca La Carrodilla. Chef Sheyla Alvarado’s signature dish, tostadas de ceviche verde, combines finely cubed jícama (Mexican turnip) and yellowtail from the fish market with homegrown coriander. And at the recently opened Fauna at boutique hotel Bruma, chef David Castro Hussong offers a modern reimagining of Mexican comfort food.

The valley’s climate also makes it an especially good place to make wine. The potential of Valle de Guadalupe was spotted early on, with the conquistador Hernán Cortés requesting vines from Spain as early as 1521. However, it’s only in the last decade that wineries have begun to flourish. That leaves plenty of space for innovation.

At Decantos Vínícola, Alonso Granados has devised the world’s first winery without a single electronic pump. He believes pumps can spoil the taste by treating the wine too roughly, so his system relies simply on a process of decanting. While he’s evangelical about his innovation, his other mission is to demystify the winemaking process for the emerging class of Mexicans who want to have a bottle of red alongside their cerveza, tequila and mezcal. 'It’s not only production that we do here,' he says. 'We want people to visit and have fun. In the old days, wine was only for kings. These days, it’s for everyone.'

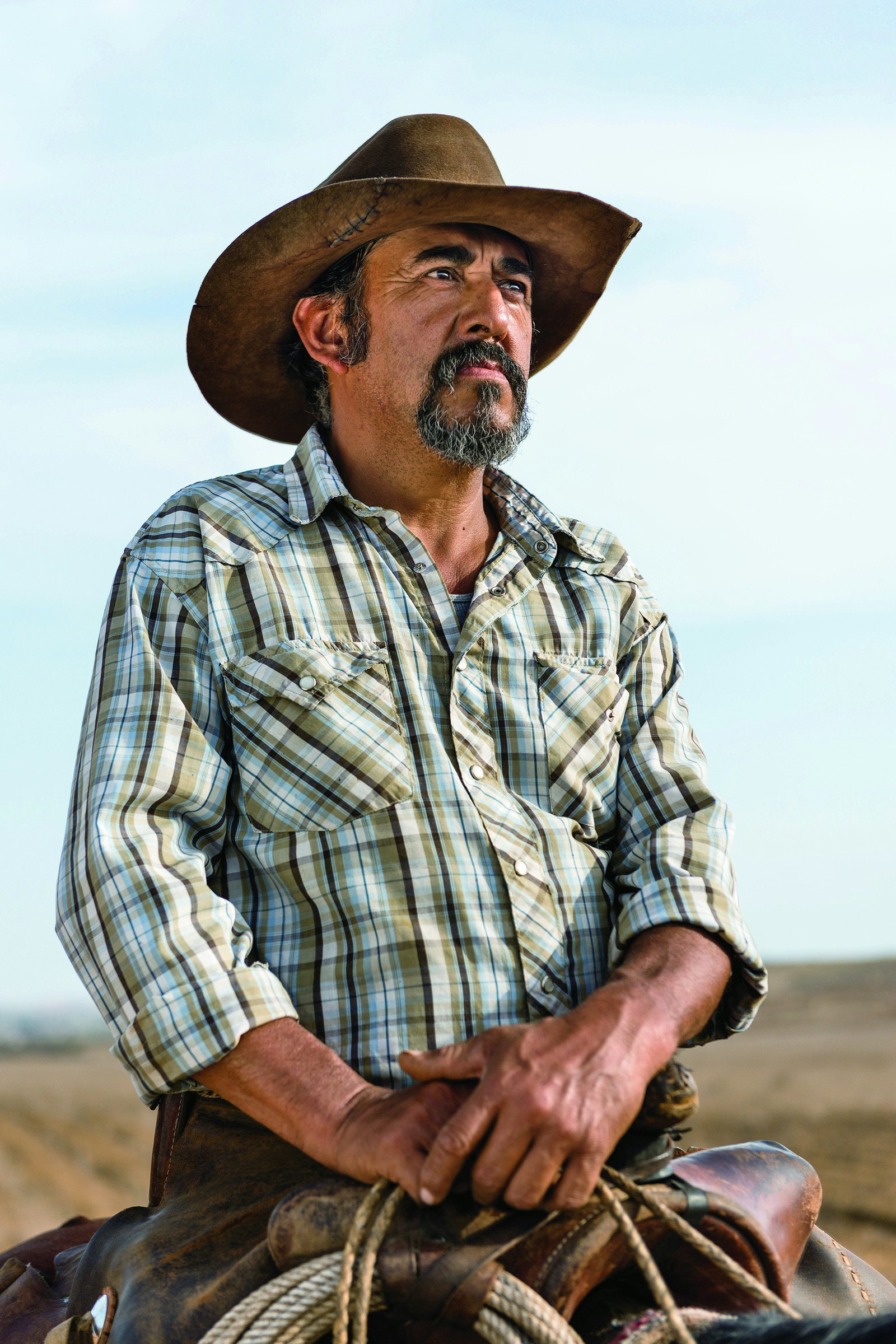

Explore the peninsula’s rugged, unspoiled heart, where condors soar and cowboys still ride.

Marcial Ruben Arce Villavicencio was eight the first time he sat on a horse. It bolted and threw him off, but he got back in the saddle. Forty-six years later he’s still riding. He’s been a cowboy all his life, just like his father and his grandfather.

Arce Villavicencio’s ranch, Rancho Las Hilachas, is just south of San Quintín and is home to 250 cows that wander freely over the 2,700 acres. It takes Arce Villavicencio and the other cowboys three months to round them up, during which time they camp and eat under the stars. They do many things the old-fashioned way here in Baja California’s dusty heartland. From a young age, the cowboys must learn to be handy with a rope. 'When an animal is wild, you have to lasso it,' explains Arce Villavicencio. 'That’s one of the toughest things to learn. It’s what makes taking care of so many animals hard. It’s like having hundreds of children.'

At least he can count on his own faithful steed Algodón (Cotton). The bay-colored criollo horse will stay with him long after the cows have been exported across the border to the U.S., where they are worth more than $800 each. Arce Villavicencio maintains that his cows are worth every penny. 'This job is satisfying, but the process of looking after a cow is a responsibility,' he says. 'You have to give them a good life, let them run and be happy. When you eat the steak, you will know by the flavor if you did well.'

Arce Villavicencio doesn’t worry that more cost-efficient commercial farming might one day kill off his timeworn way of life. 'We’re not afraid of competition from farms like that, because we think people value this more.'

With Arce Villavicencio herding his cows through the foothills, the Sierra de San Pedro Mártir rises behind him on the horizon. The mountain range is home to a 170,000-acre national park, which is a sanctuary for bighorn sheep and mule deer, as well as cougars, bobcats and coyotes. The thick pine forests, punctuated occasionally by craggy rock faces, make the perfect environment for hikers and horseback riders.

At the very top of the park stand several deep-space telescopes that make up the National Astronomical Observatory. The location was chosen because of its lack of nighttime cloud cover and light pollution, meaning that professional astronomers and amateur stargazers can view the vast Milky Way. And that’s not the only impressive sight to be seen above. Near the entrance to the park is a rocky outcrop where California condors gather. In most places the graceful birds only can be spotted circling high in the air, but here they swoop low overhead, their huge wings making a loud crack as they glide downward.

Back on the ranch, Arce Villavicencio tends to his own animals. Then, with the last of the day’s sunlight fading away, he takes his place on an old sofa outside to open a few beers with his son and brother-in-law. 'I can’t imagine going anywhere else,' he says. 'We don’t do this for tourism. This is the way we live. If you want to learn about ranches and the cowboy lifestyle, then this is the best place to come because we’re not pretending. That’s the special thing about this place.'

Immerse yourself in the natural world by swimming with whale sharks and sea lions in the Sea of Cortez.

At first it’s just a shadow moving in the water. It seems impossibly big: 26, maybe 30 feet. Dive under the surface and you can come face to face with more than 20 tons of muscle and cartilage with fins – the broad mouth sucking in plankton as it reaches up toward the light, the remoras clinging to its white-spotted body, the graceful stroke of its huge tail fin as it glides through the water. It moves leisurely, averaging around three mph, so for a little while you can swim alongside it, kicking your scuba fins hard to keep pace. It’s not just a big fish, but the biggest fish of them all: the whale shark.

It is a majestic sight in a place that is overrun with majestic sights. The Sea of Cortez, the hundred-mile-wide strip of water between Baja California and the Mexican mainland, was a favorite of the great ocean conservationist Jacques Cousteau. He called it 'the world’s aquarium.' It is home to a vast panoply of sea creatures, with some 900 species of fish and 32 types of marine mammals living, eating and breeding here.

It’s not uncommon to spot sea turtles, manta rays and even gray whales. You can swim with sea lions, who bark and tussle like a pack of aquatic dogs, and anglers come here in pursuit of yellowtail, red snapper and grouper. The fishing is so good even the birds join in. Brown pelicans and blue-footed boobies soar through the air and then suddenly dive, freefalling out of the sky and snatching up their prey.

It is experiences like these that encouraged Ricardo Arce to start his eponymous diving tour company in his hometown of Bahía de los Ángeles. 'I grew up here and I’ve been diving for 21 years,' he says. 'I wanted people to have the same experiences that I’ve had.' Bahía de los Ángeles is a small fishing town of just 800 people beside the mountains of the Sierra de San Borja. Its isolation makes it such a perfect place to get close to the Sea of Cortez’s many wonders.

As a tour group returns by boat after a day at sea, the town is barely visible on the shoreline. 'A regular day here means getting up early to give a tour, then having a chilled life,' says Arce with a shrug. 'It’s a relaxing place.'

This has not happened by accident. The community of Bahía de los Angeles consistently comes together to fight plans to make the town into a more commercial resort. 'We’re concerned about development. It worries us,' Arce says. 'We think the area has been conserved very well like this, so we don’t want it to grow that much. There have been lots of projects that have tried to get in here, but as a community we didn’t want them. We’re very selective about the sort of tourism we want to attract. We don’t want spring breakers or the party crowd. We only want people who are really interested in getting to know nature.'

Places like Bahía de los Ángeles are crucially important because the whale shark is an endangered species. Arce is a member of a local conservation group, Pejesapo, which since 2008 has worked to preserve the whale shark’s habitat and to count their numbers. The sharks are most commonly seen between June and December, and at the season’s peak Arce has seen as many as 55 in one day. 'It’s a good feeding ground here,' he explains. 'We used to think that they just ate plankton, but by filming them here we found out they eat bigger fish too.'

There are only a couple of very small hotels in the town, which means that for most of the year there are likely to be more whale sharks here than tourists. Arce is happy to keep it that way. 'We try to set an example for the next generation about how you should do things,' he says. 'We want to show them that this is how you protect the environment.'

Uncover incredible history through the churches built by Jesuit missionaries in the 17th and 18th centuries.

The midday sun beats down on the white facade of the Misión San Ignacio, the Spanish mission’s door creaks open. The church’s warden, Francisco Zúñiga, steps through, gesturing to the aged wood. 'This is original,' he says, 'from 1728.'

That makes the door older than many towns here in Baja California. The largest city on the peninsula, Tijuana, was founded in 1889. While the native history here is long – there are cave paintings by the Cochimí people that are thought to date from as far back as 7,500 years ago – the history of modern settlements didn’t begin until the arrival of Jesuit missionaries from mainland Mexico in 1683. It was 1697 before they founded the first Spanish town on the peninsula, Loreto, a 3½-hour drive south from San Ignacio.

They came by boat from Sinaloa, unsure whether they were approaching an island or a peninsula. They first landed at modern-day La Paz, but were driven north by the native Pericúes and Guaycura people, and eventually ended up near Loreto. Their first attempt at constructing a church, Misión San Bruno, was abandoned in 1685 due to a shortage of food and water.

In 1697, another Jesuit group, led by Italian priest Juan María de Salvatierra, arrived in Loreto and tried again to construct a mission. This church, the Misión de Nuestra Señora de Loreto Conchó, or Mission Loreto, proved more successful and the settlement became the first Spanish-claimed territory on the peninsula – and the base from which the missionaries expanded their evangelical work throughout the region. The church still stands in Loreto, next to a museum dedicated to the history of the Jesuits. However, as the museum’s custodian Hernán Murillo explains, the missionaries who made it as far north as San Ignacio saw a fall in the number of their flock due to an unforeseen danger, which would be repeated across the continent.

'There’s an expression here: ‘The bells that call the wind,’' he says. 'The San Ignacio mission was started by the Jesuits and finished by the Franciscans, but by the time they completed the mission, they were seeing the effects of Westerners arriving with diseases that the locals didn’t have immunity to. By the time the mission was finished there weren’t many people left to go to the church. That’s why we say there were only bells to call the wind.'

Today, the village surrounding the Misión San Ignacio is home to just 700 people, while Loreto is a larger town of 15,000. Until 1777 Loreto governed the whole state, which at the time stretched all the way up into what is now the U.S. Much of the town’s architecture still bears out that colonial legacy. Loreto is easy to explore on foot and is arranged around a central square, Plaza Juárez. From there it’s just a short stroll up the tree-lined Avenida Salvatierra to the mission. Restored several times after centuries of earthquake damage, it retains an inscription above the door that attests to how important it once was, translating as 'The head and mother church of the missions of upper and lower California.' Inside, behind the altar, sits an elaborately decorated baroque retablo that was transported here at great expense from Mexico City.

For a town with such a rich history, Loreto is now a peaceful place. As dusk falls in the Plaza Juárez, couples sit outside a restaurant named 1697 sipping beers as they listen to a guitar player. They gaze across the square to the imposing Spanish Colonial city hall. Underneath the word Loreto it bears a stone legend, naming the town the Capital Histórica de las Californias (Historic Capital of the Californias). But now, like the beer drinkers themselves, it is a town left alone with its memories.

Swim, kayak or paddleboard your way around the white-sand beaches and rocky coastlines.

The sun is dipping low in the sky over Balandra Beach, 17 miles north of La Paz, but the groups of friends and families who’ve come to while away a Sunday afternoon by the sea are determined to eke out every last moment of the day’s heat. As the tide comes in, two men lift their plastic picnic table up out of ankle-deep water and carry it to shore, a half-empty bottle of rum still balanced on it precariously.

Farther up the beach, a group of teenage acrobats from Tijuana are taking turns throwing each other, pirouetting high into the air, until inevitably – perhaps the result of too many cervezas – they miss their catch. The fallen gymnast laughs it off, rolling over in the soft, white sand. American pop music pumps from an unseen stereo. Kayaks of green and orange return to the bay, easy to spot against the turquoise sea. As sunset approaches, the sky becomes a miraculous shade of red. Even the clouds appear to have been dyed pink, like cotton candy. Families take turns traipsing to the far end of the bay to snap the obligatory selfies in front of Balandra’s signature mushroom rock.

As they clamber back up the dusty brown slopes dotted with cardón cactuses to where they’ve left their cars, it is easy to see why people are drawn here from across Mexico, attracted by the white sand and the warm, azure water. A cracked tile sign near some government-built sunshades declares that they were 'Hecho con Solidaridad,' made with solidarity. It’s a beach that welcomes all with open arms.

By contrast, out at sea lie some more exclusive beaches. Espíritu Santo, a 31-square-mile island in the Sea of Cortez ringed by mangroves and volcanic rock formations, was declared a Unesco biosphere reserve in 1995, and the number of visitors there is carefully limited. It is officially uninhabited, although at certain times of the year it is possible to stay overnight on the island at Camp Cecil, a series of safari tents set up with real beds and furniture on the long stretch of La Bonanza Beach. Live-in chefs Giovanni and Ivan serve up excellent Baja Med fare, and can organize everything from kayaking and snorkeling to bird-watching and nature hikes.

Espíritu Santo is an hour by motorboat from La Paz, and it’s common to see schools of dolphins playing in the boat’s wake. For the more adventurous, it’s also possible to reach the island by kayak or stand-up paddleboard. The next day in La Paz, on the long stretch of beach in front of the city’s Malecón, paddleboard instructor Sergio García, of Harker Board Co., is giving enthusiastic lessons to the uninitiated. A former professional basketball player from Chihuahua, he moved to La Paz seven years ago, drawn like many others by the relaxed beach lifestyle.

'I first visited La Paz when I was 16,' he says, keeping a watchful eye on his students out in the bay. 'I knew it was a beautiful place, so I always thought I’d like to come back and make my life here. It’s a small town growing up quickly. You have a good quality of life here, better than in the other states of Mexico. It’s a really peaceful place, tranquil and calm.'

García learned to paddleboard when he moved here, and now the sport has taken over his life. 'In my free time I paddleboard as well!' he says with a laugh. 'La Paz is a perfect place for stand-up paddleboarding because you have warm water all the time. Sometimes there is wind and sometimes you have waves, so it’s good for beginners and for experts.' He tosses his board into the water and clambers on, then with long strokes paddles swiftly out into the bay. Like life itself in this place where the desert meets the sea, he makes it look easy.

Kevin EG Perry traveled to Baja California, Mexico with support from visitmexico.com. Lonely Planet contributors do not accept freebies in exchange for positive coverage.

https://shop.lonelyplanet.com/products/mexico-travel-guide-15/

Plan with a local