Grief on the Nile: What it is like to get the worst news on a dream trip

Sep 9, 2025 • 12 min read

The moon at sunrise on the Nile River as seen from aboard a riverboat in Luxor, Egypt. Jessica Lockhart/Lonely Planet

It’s nearly midnight, but the line to check into the Four Seasons Cairo still stretches through the lobby. I lean against my suitcase, my eyes burning with the fatigue of travel, and connect to the hotel’s wi-fi to pass the time. I’ve only been offline for six hours, but my phone comes back to life with a long string of missed calls and WhatsApp messages. My heart sinks into my gut.

They’re all to deliver the same course-altering message: sometime in the next 24 to 48 hours, my mom will take her last breath.

Eight weeks earlier, I’d flown from New Zealand – where I live – back to Canada to be at my mom’s side. The diagnosis had been sudden, unexpected and devastating. I’d rubbed her back as industrial-yellow chemicals slowly dripped, dripped, dripped their way in. But after several rounds of aggressive chemotherapy, it became clear that she’d never again plod alongside me on a hiking trail in Newfoundland or sit in a public park in Vietnam, tasting durian on a dare.

I had known she was going to die. I just had no idea it would be so soon.

In the privacy of my hotel room – beside the empty twin bed that should have been hers – the tears become a river. My sorrow feels capable of filling the 6,800km Nile from source to sea – salty droplets that would stretch all the way from Lake Victoria to the Mediterranean Sea. They flow wet and hot, forming estuaries in the fresh white sheets.

The tears aren’t just for my mom. They’re for the loss of my once-in-a-lifetime trip to Egypt; one I’ve been dreaming of since childhood. One that has seemingly ended before it even started.

The doctors said she had six more months. Why couldn’t she have waited two more weeks?

The thought brings a fresh wave of tears, a new torrent that tastes bitter with shame. Surely, I’m selfish for wanting to stay.

But I know that time isn’t on my side. Trying to get back to Canada now is a gamble. Staying, at the very least, will be a brief intermission before what’s to come: hugging strangers at a funeral; selling her belongings; and countless meetings with banks, lawyers and accountants. Yet I also know that if I don’t leave now, I could end up miserable and trapped on a boat full of strangers with no chance of escape.

Torn, I call my aunt. She puts the phone up to my mom’s unconscious form so I can say my goodbyes.

Then, my aunt’s voice is at the other end of the line.

“She would want you to stay.”

The splendors of living

The next morning, after picking at a bowl of flatbread and ful (an Egyptian breakfast staple of fava beans, oil and spices), I make my way up to the hotel’s conference room. It buzzes with guests aboard Uniworld’s 12-day “Splendors of Egypt & The Nile” tour becoming fast friends.

I want to blend in, but my tongue feels thick in my mouth. I don’t know how to hold my face. Grief is contagious and I am Patient Zero. There’s also the judgment. Who am I to board a cruise when my mom lays dying? Shouldn’t I be channeling Queen Victoria, who famously mourned her late husband for 40 years?

To divulge my truth would mean being examined over every action: for smiling and laughing, for taking a selfie in front of the Sphinx, for helping myself to seconds at the buffet. I want to gain at least 5lbs from the amount of moutabel I plan to consume.

No, I determine. No one – save for the small group of journalists that I’m traveling with – needs to know the truth. I can’t risk being perceived as living when my mom is being denied that same luxury.

It was a privilege that she didn’t often take for granted. My mom loved to travel. With my dad, she cruised around the bottom of Cape Horn, went on safari in Kenya, took the train through Mexico and sailed around the British Virgin Islands. When he died, my mom tried to carry on by signing up for women-only tour groups. But she felt lonely, she told me. She hated traveling alone.

I understood the assignment

Our trips became an annual affair, which I’d quietly bemoan to my partner. I loved my mom and knew I was lucky to spend time with her, but our relationship wasn’t always easy. It wasn’t unusual for her to invite herself to join me at a conference or show up at my hotel unannounced when I was on a group press trip.

But when I called to invite her to Egypt, it was with genuine pleasure. It would be the ideal trip for her idiosyncrasies – one where her penchant for history, love of the macabre and tendency to ask cringey questions would be entirely acceptable.

She was just as excited.

“This gives me a reason to get out of bed,” she said, her voice brightening. I knew she’d been feeling unwell, but I had attributed her fatigue to midwinter depression. The lure of an adventure would be enough to snap her out of it.

Two days later, she was in the hospital.

Two months later, she would be dead.

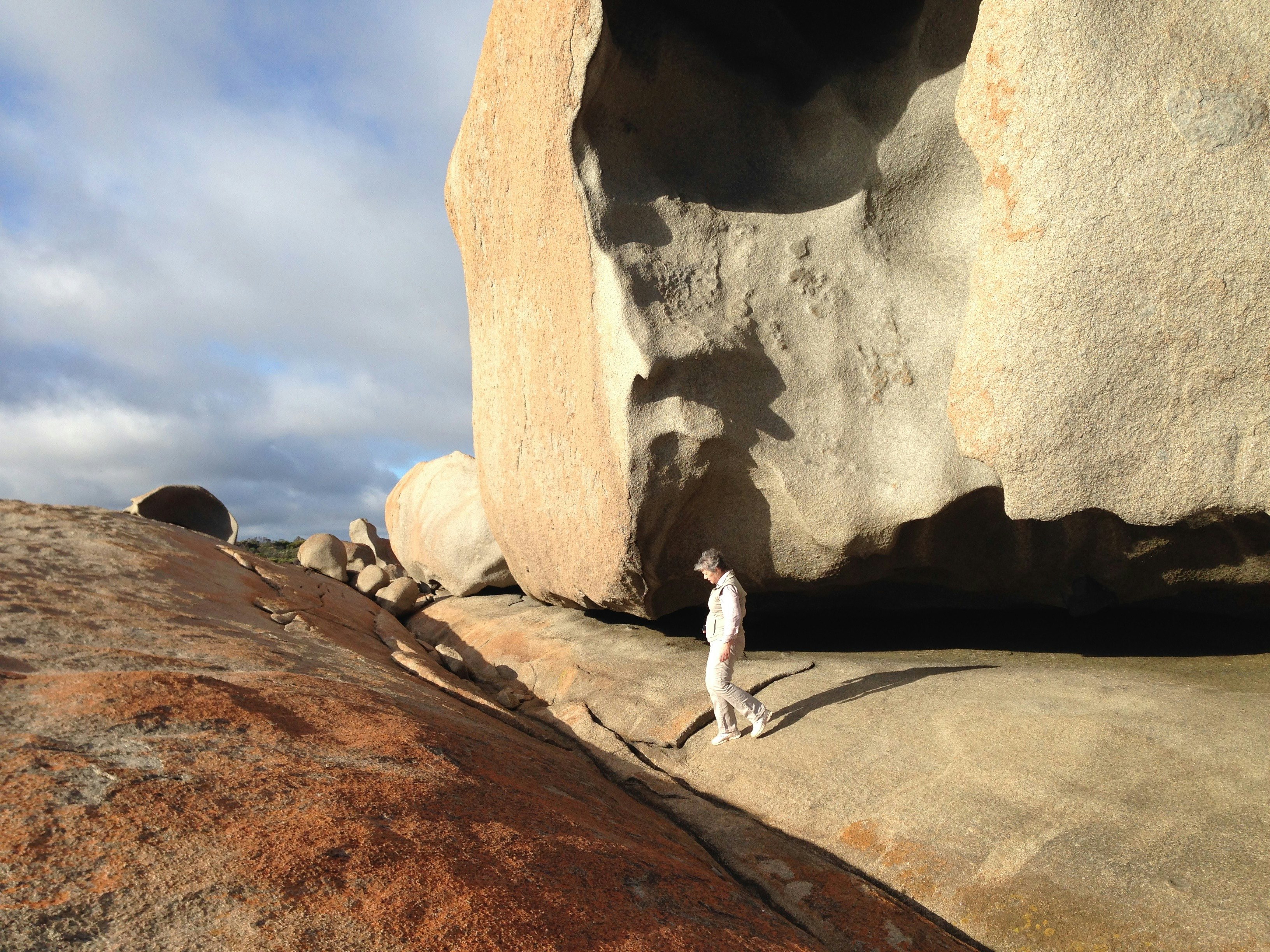

After flying to Luxor, we board our boat for the week: the SS Sphinx, a 42-suite ship complete with a massage room, swimming pool and two restaurants. Down the mirrored hallway, I find my room. Fluffy white pillows encased in Egyptian cotton lay beneath a carved wooden ceiling. Atop a table inlaid with mother-of-pearl sits a bowl of fresh fruit, courtesy of the Nile’s nutrient-rich shores. I pull my balconette doors wide, the gauzy white curtains billowing around me. Below, the Nile maps our path, its banks dotted with palm trees and earthen-brick homes, made from the river’s mud.

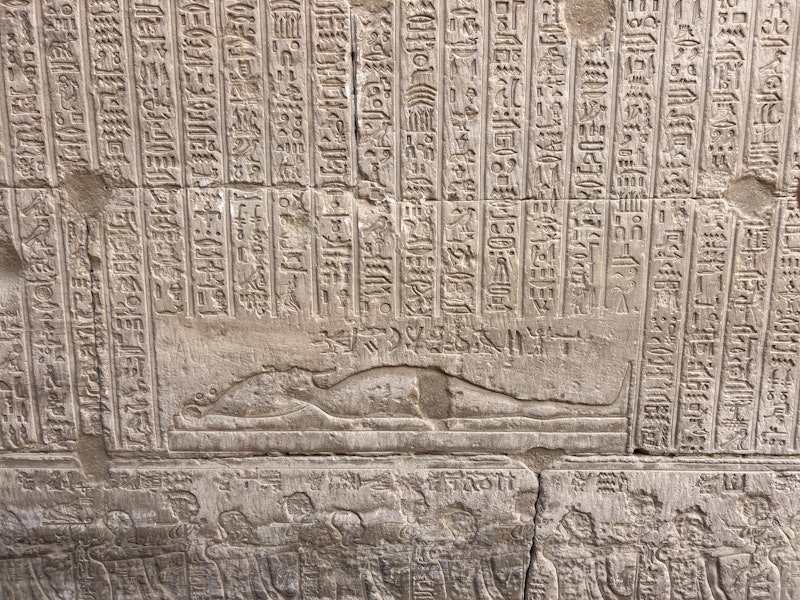

Our first stop is in Dendera to the north, to visit the temple of Hathor, the goddess of fertility and motherhood. Long ago defaced by Christians eager to eliminate pagan symbols, her head sits atop the temple’s soaring columns. She’s been rendered blind, but her cow ears stretch out eagerly, hoping to catch bits of our conversation. It’s a classic mom move. I ignore her and instead focus on the long, slender figure of Nut, the goddess of the heavens. Her body wraps around the ceiling, the sun at her lips; a promise to deliver another day.

On the temple’s rooftop, our Egyptologist, Hazem Khalaf, points out the hieroglyphics that tell the tragic love story of Osiris and Isis. After Osiris was murdered by his brother Seth, Isis came to represent mourning in funerary rites. When someone died, professional mourners – always childless women – would be hired to play the part of Isis and her sister, Nephthys.

“There are still professional mourners in Egypt, who scream and cry in a village so people know someone has died,” says Khalaf.

According to Anita Isalska, author of Lonely Planet’s Guide to Death, Grief and Rebirth, these “people paid to weep” help others see the depth of our devotion when it’s difficult to process our own emotions.

“This is the paradox that professional mourners can resolve: they fulfil our need to express grief, even if we’re incapable of doing so ourselves,” writes Isalska.

Would I be forgiven for staying in Egypt if I had hired a professional mourner? I ask Hathor’s faceless head. She’s no longer listening. Classic mom.

Back on the boat we turn south towards Luxor, scenes from the Nile sliding past. Children swim out towards the boat, their screams of glee cutting through the dry, hot air. Water buffalo cool off amongst the papyrus reeds, their owners held aloft in boats. Women in abayas pause from doing laundry to stand and wave. All around us, there is life.

I film a time-lapse of the sun sinking beneath the horizon, Nut’s work in motion. Tomorrow, she’ll deliver us another day.

But my mom won’t be here to see it. Ten thousand kilometers away, she takes her final trip.

Visiting the Valley of the Grief

The next morning, our bus winds its way up towards the Valley of the Kings, the site of at least 62 tombs including King Tutankhamun. We pass carts pulled by donkeys, watermelons stacked beneath underpasses and huge bags of juicy oranges hanging outside shops. At the side of the road, police pause their duty to attend to another one – facing Qibla and praying.

Over the bus’s speaker, Khalaf begins to outline the process of mummification.

First, the brain was pulled out through the eyes. (I think of her brain, ridden with tumors.) The eyes were replaced with semiprecious stones. (For months she had complained about her vision; one of the first symptoms.) The stomach, liver, lungs and intestines (she had wanted her organs donated) were preserved in canopic jars so they could be used in the afterlife.

God, she would find this fascinating.

It’s this final thought that breaks me. I slouch low in my seat, sliding on sunglasses to hide the tears.

I was a fool to think this trip would be a distraction. Instead, I’ve somehow managed to end up in the one destination where every single day will be dedicated in some way to discussing death, mourning and the afterlife.

Even the word “mummy” becomes a trigger. Before I left for Egypt, my brother had flown in to take my place at my mom’s side. We didn’t know how long she was going to be sick, so I’d taken the advice she had drilled into our heads from childhood: you can’t help others if you don’t help yourself first.

And I needed help. After a month, I was drained. The bags under my eyes were capable of carrying small children. The plan was that my brother would stay until I got back from Egypt and then we would trade off once again. I showed him how I helped her brush her teeth. I trimmed her nails and rubbed lotion into her feet. When it was time to go, I wrapped the hospital sheet around her figure, tucking the ends under her shoulders and feet.

“You look like a mummy,” my brother teased.

A cheeky grin spilled across my mom’s face. “I am your mommy,” she said. Even when the cancer had robbed her brain of so much, she was never one to pass up a solid pun.

Everywhere I turn, there she is

It’s not just the tombs, though. In Egypt, everywhere I turn, there she is. We go for high tea (one of her favorite activities) at the Old Cataract Hotel, where Agatha Christie (who my mom loved; murder mysteries being one of her favorite genres) wrote Death on the Nile.

Another day, on the way to the Abu Simbel temple complex, I sit next to a woman roughly my age traveling with her mom. I can sense their love for one another – but also the sense of obligation.

What I wouldn’t give to feel that prickle of annoyance.

At night, I join the other journalists at the boat’s “galabeya party” (named for the loose-flowing garments worn in the Nile Valley), where everyone tries traditional dancing before the playlist devolves – as all good playlists do – into the Macarena. Music still pumping in the SS Sphinx’s lounge, I excuse myself early. Up in my cabin, I call my brother to discuss the funeral. I write the obituary. I start making notes for the eulogy.

Then, exhausted, I post stories to Instagram of earlier that afternoon. There’d been a sandstorm, carrying grit all the way from the Sahara to the upper deck of our boat. In the photo, I’m poolside, smiling in a bikini. The entire storm, swirling all around me, is obscured from the shot.

If the Nile could be dammed to prevent floods, so too, surely, can my grief.

“Everyone grieves in their own way”

One morning, I open Instagram to see a suggested post. In Dan Caffee’s latest Reel, his three blonde daughters wander through Cairo’s bazaar, tumble down the Sahara’s dunes and pose beside two colossal statues of Pharaoh Rameses II at Luxor temple. It appears I’ve been trailing the Caffees all week.

It’s the caption, though, that makes me pause: “Everyone grieves in their own way.”

Three weeks before the American family boarded a plane to Cairo, Caffee’s wife, Elise, died from injuries sustained from a car accident in Mexico. But the spring break trip to Egypt – planned by Elise – had already been booked.

“We talked as a family and we all agreed that [Elise] would really want us to go on the trip,” wrote Caffee on Instagram. “For us, adventure is the best medicine (well, that and lots of therapy).”

For once, I’m not annoyed that the algorithm knows all. If those three girls were brave enough to get on the plane, then why am I beating myself up for making the same choice?

I also start to see that I’m not the only person on the boat hiding behind sunglasses and smiles.

At lunch, I ask a fellow passenger a question about her husband. Her face falters.

“I’m not sure that I have a husband to go home to,” she confides. Her marriage, she thinks, is likely over. She’s mourning what was lost and what could have been – but in what she’s losing, there’s also a chance for a new, better beginning.

A young woman talks to me about her recent miscarriage, while another shares that her own mother died when she was just a teenager. I watch a middle-age couple cuddle on the sunloungers – a surprisingly intimate public display of affection. I later learn that she has cancer.

We’re all carrying grief: for loved ones lost, for opportunities missed and for paths not taken.

Somewhere around the Esna Lock, I let my guilt sink to the bottom of the Nile.

She would have wanted me to stay

For the last week, I’ve been worried about the judgment of others. Really, I was trapped in a cycle of judging myself. And without the guilt, I now have room to sit in my grief.

Slowly, I start sharing my story with some of the other passengers. I post the obituary on my social media with a reminder that “grief looks different for everyone.” And finally, I take a note from Queen Victoria, who popularized mourning jewelry (although the Egyptians did it first).

Isis feels too obvious. So, with the help of the ship’s on-board jeweler, I select a gold scarab beetle with a blue lapis stone, threaded on a delicate Eye of Horus chain. Favored by the ancient Egyptians, the beetles were revered as a symbol of rebirth, thanks to their ability to hatch young from the heavy dung balls they push around.

It feels apropos. Now, every time I see the scarab glinting at my throat, I’m reminded that we’re all pushing around heavy shit. And, in time, there’s a chance that new life will emerge from the pain.

Jessica Lockhart visited Egypt at the invitation of Uniworld. Lonely Planet does not accept freebies for positive coverage.