Australia’s ‘sorry rocks’ lead to reckoning and reconnection

Jun 28, 2025 • 11 min read

Photo illustration by Matthew Johnston/Lonely Planet; Images: Jessica Korteman, Getty, Shutterstock (2)

“He was a very broken man,” says Tanya Charles, a Mutthi Mutthi Elder and Discovery Ranger at Australia’s Mungo National Park. His face was weathered with despair, desperation and defeat; in his despondent hands he held two black stone axes.

Around ten hours west of Sydney and deep within the New South Wales interior, Mungo National Park is jointly managed by the state’s National Parks and Wildlife Service (NPWS) and the three Aboriginal tribal groups, the Paakantji, Ngiyampaa and Mutthi Mutthi. Mungo National Park forms part of the UNESCO-listed Willandra Lakes Region World Heritage Area and is an active Indigenous archaeological site.

For Charles, a chance meeting with the man with the axes, on a muddied Mungo roadside, became an extraordinary account of face-to-face restitution.

She tells me about the encounter as we sit down to discuss the park’s taken-and-returned items; what it means to atone mindfully and consciously in the face of entrenched colonialism; and what happens when we center cultural and environmental wealth through sustainable tourism practices.

A journey of atonement

The first time Alex* was here, there had been joie de vivre to his visit. He had a carefree demeanor that flowed from the liberty of fortunate circumstances – a caring wife, a lucrative job, a comfortable home and his own vehicle to take him to “adventurous” places like Mungo.

Twenty years later, he stood soaked and weary from a 375-mile bicycle ride from Melbourne and two decades of calamity. He was en route to Mungo Visitor Centre, clutching the stone cutting tools he’d taken on that last visit.

This time, he was seeking repentance.

“I knew immediately where he took them from, because I found them axes,” says Charles, whose role as a ranger includes documenting Indigenous artifacts found in the park. Following the Aboriginal belief that everything has its place within the landscape, she had left them in situ.

Taking the axes was a decision Alex would later say ruined his life. Removing an item from its spiritual home is believed to attract bad fortune as it upsets Ancestor spirits and the natural order of a sacred place. Since grabbing the chiseled stone axes as souvenirs in the early 2000s, misfortune followed Alex wherever he went. He lost his marriage, his home, his job and his car, among other hardships.

But the universe seemingly aligned to bring Alex together with Tanya Charles; they happened to cross paths on a park road that was set to close shortly, because of the rain. He’d made his way to Mungo by pushbike – not for fun or fitness, but because it was the only option he could afford.

Destitute and depleted, the stormy weather couldn’t deter Alex from making the hurried journey before the roads turned to sludge and access to the park was cut off.

It was there he explained what compelled him to ride for days in the rain to return the artifacts. It was an anguished plea for the bad luck to finally shift. “I just had to return them,” he said.

Eons of culture and connection

Erosion and wind-swept sands, a result of land-clearing since Europeans first arrived, constantly reveal new archaeologically and culturally significant sites at Mungo National Park. In the 1960s and ‘70s it was the discovery of 42,000-year-old human remains, dubbed Mungo Man and Mungo Lady, that completely re-wrote the record of Aboriginal existence across the continent, a history Charles believes goes back much further.

The evidence, she says, is in the sand. Charles gives authorized tours of the Walls of China, otherworldly clay formations on sandy dunes named after Chinese workers who built a woolshed in the area in the mid-1800s.

Wind and rain constantly shape and move the layered landscape, revealing fossilized aquatic life from the now-dry lakebed of Lake Mungo, along with spearheads, human footprints and remains of ancient campfires.

But access to Mungo and the privilege of walking this hallowed ground bearing the physical remnants of Indigenous history come with a caveat: removing objects anywhere in the park is strictly prohibited. Despite clear signage warning visitors, Alex’s impulse to take items is not uncommon. Nor is the compulsion to later return them. Protected Indigenous sites across Australia, like Mungo, receive returned items on a near-daily basis. They include rocks, sand, twigs and foliage, fossils and other objects related to long-standing Aboriginal presence on Country.

“Country” is an Indigenous term that describes not only the physical landscape, waterways and sky, but also creation stories, songlines, language, lore and law. It is indicative of the holistic way Aboriginal Australians view this world and the intrinsic relationship between one action and its impact on another.

Charles pauses our conversation to point out a large red river gum by the Visitor Centre. “When it rains, I put my ear up to its trunk,” she says. “It’s the most incredible sound, to hear a tree drink.”

It’s hard not to notice Charlesʻ synchronicity with Country and, in contrast, the disconnect that has led non-Indigenous visitors to view Mungo as a souvenir store.

Conscience rocks

Not everyone believes in curses, but a spate of unfortunate events is often cited for an object’s return. Many attribute their misfortune to at least some kind of karmic reckoning brought on by severing an item’s connection to Country.

But bad luck or not, there's a growing understanding that disharmony with the natural and spiritual world is disrespectful to Indigenous communities, and looting extends to the taking of stones and sand.

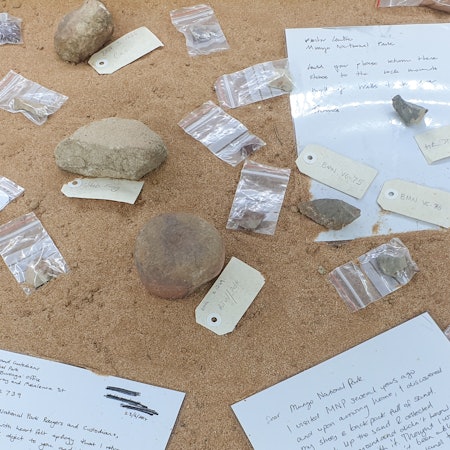

Usually accompanied by a letter of apology, returned items have become known as “sorry rocks,” but Charles refers to them by a different name.

“I call them conscience rocks,” she says, “because those returning them are seeking to free themselves of the weight of their actions.” Adept at reading behaviors in her tour groups, when she receives another “conscience package” from a recent tour participant, Charles immediately knows who sent it.

“Dear Tanya, I enclose a five-million-year-old piece of rock from Lake Mungo. I know you said not to – I did and I am sincerely apologetic. Particularly as I spent a week in hospital on my return from Mungo at Easter time after crashing my bicycle into a car! I can’t say you didn’t warn me. I have a fascination for rocks and collect them in my travels from time to time.”

The letter, stripped of identifying markers, now sits in a display cabinet in the Visitor Centre along with a small selection of correspondence from other conscience rock returners. That was an idea of Charles', designed to help stem the number of items removed from the park.

Return is just the beginning

“To the Traditional Owners of the land and those who continue to care for it,” another letter begins. “Since [travelling to Mungo National Park], our lives have been beset by ongoing and serious issues. I hope the return of these items will be welcomed!”

While indeed well received, Charles says returning the objects is only the first step in an item’s return to Country.

Charles knew from where Alex and the first letter writer had taken the items, but conscience rocks are often returned without the specifics needed to repatriate them to Country. Most items are sent via post or are handed into police stations or passed on to a visiting friend or relative to return on another’s behalf. The Visitor Centre has become a repository for conscience rocks, securely storing the most recently returned items.

“It’s not as simple as returning them anywhere,” Charles says. Without knowing the precise location of their removal, the lengthy process of determining what to do with the objects in culturally appropriate ways creates a huge amount of work for park staff.

Unable to keep up with the rate of returns, Uluṟu-Kata Tjuṯa National Park in the Northern Territory has resorted to placing items of unknown origin in a designated neutral space, where they can be on Country, but not upset local Aṉangu law/lore, which dictates the relationships between people and the land, and respectful ways to interact with the natural environment.

Symptoms of deeper injustice

“It was wrong for me to move [this stone] from where I found it,” another conscience-letter writer reflects. “In doing so, I have seen part of myself that I am ashamed of...”

“While at Mungo, I thought about how [Mungo] had been cared for, for thousands of years. I thought about the harm that has been done in Australia since white settlement. Then, with taking this object, it occurred to me that I too contribute to this harm.”

There is much to be learned here, a deeper conversation that non-Indigenous travelers need to have about colonization, not as a historical event but a continued paradigm, and what responsible and conscious tourism looks like in a world striving to do better than its forebears.

As I read the letters, I feel a sense of unease. There’s an uncomfortable truth that, among other things, the removal of items stems from an ongoing perceived liberty to take – to possess, hoard and desecrate – that overruns a collective wealth. Each rock and baggie of sand is another small act of conquest; colonization, pervasive in many daily forms.

Still, Charles welcomes visitors to Mungo and the return of items with grace. And her stories, tours and displays at the Visitor Centre are making a difference in the attitudes of those who come here. More people than ever are learning about Mungo through the park’s Aboriginal Discovery Tours and experiencing first hand why this landscape is a place that requires respect and protection.

It may not have the flashy facilities or attractions of some larger national parks, but on each visit to Mungo I have an all-encompassing feeling – a presence and perceptiveness that beckons me to listen.

“It’s the truth-telling of the place,” says Charles. “There’s a true history here. You can’t tamper with it. You can’t replace it.”

The land as a mirror

Mungo speaks through its geology and archaeological testimony, and continues to converse with us through its daily presentation.

Charles firmly believes the environment shifts based on its reception to those on it. If the landscape doesn’t reveal itself – if the sand doesn’t clear a path to show what lay beneath an area on a given day – she believes it wasn’t supposed to. “Perhaps it sensed that someone on the tour was not respectful,” she says.

Before society transitioned from traditional practices to what Charles refers to as the “new world,” she says there were no liars on Country. “If you lied, you got speared,” she says. “Indigenous law was that strict.”

Today, Mungo continues to be watched over by Ancestors, inviting visitors to be on Country in a spirit of honesty, gratitude and respect. In many ways, Mungo holds a mirror up to human behavior and decides if it likes what is reflected back.

Truth-telling requires radical accountability, and that requires standing in that truth. When it comes to returning taken items, there is an opportunity to make amends and lessen the burden placed on Traditional Custodians by providing the information that will allow the removed items to find their rightful place back in the landscape. However, there’s rarely a substitute for doing that yourself.

“If you are going to return an item, please assist us by doing it yourself in person,” Charles says. “It’s for your healing too.”

Charles frequently speaks with those who have carried the guilt, and sometimes bad luck, of taking from the park. In many cases they have borne the burden for years. At Uluṟu-Kata Tjuṯa National Park, returned items usually come in within 5 to 10 years of being taken. But, like with Alex and the Mungo axes, it can span decades.

In addition to those returning ”conscience” objects they took themselves, some items now come in from grown children or grandchildren, who remember a relative pocketing something on a childhood holiday or who have come into possession of an item through an estate. In those cases, they’re looking to right the wrongs of their lineage.

“It’s always amazing when that happens,” says Charles.

Listening and understanding

Conscience returns are an opportunity for tangible moments of connection that a rock in an envelope could never bridge.

“I really hope that by coming here and speaking those words, Alex was able to turn his life around,” Charles says with genuine care. “Maybe one day he’ll visit again and I’ll get to hear all about the new chapter in his life.”

Reverence and understanding underpins everything.

“Mungo is a place to be respected,” says Charles with conviction. “People would think twice about pulling branches from shrubs if they looked closely to see it as a habitat for a variety of species.

“Ant nests on walking tracks aren’t an annoyance when we acknowledge them as nature’s perfect regeneration setup – holes to underground colonies are an ideal cavity for seeds to spring forth new foliage after rains.”

The land speaks here, begging us to move slowly and tread lightly. In return, when we honor it, the land offers wisdom, energy and spiritual sustenance.

"You don’t need to take from the park to feel it, to learn from it," says Charles.

Just as the gum tree drinks, the landscape chatters in its own tongue. Are we ready to be still, put our ears to it and truly listen to what it’s been telling us all along?

*pseudonym