April 26 marks the 35th anniversary of the Chernobyl nuclear powerplant disaster in Ukraine (then in the Soviet Union). The explosion was the worst nuclear disaster the world had known and an exclusion zone was established in the surrounding region, including neighboring Belarus, which experienced much fallout as a result of a radiation wind plume.

While the 2019 HBO series Chernobyl sparked an increase in interest in the Ukrainian site, the Belarusian section only opened to small numbers of tourists in late 2018. Travel writer Richard Collett went to Belarus to visit the exclusion zone. He recounts his experience.

It’s quiet in Dronki. Eerily so. The only sounds that break the hushed silence are the rustle of trees and the methodical, high-pitched beeps of a Geiger counter.

Dronki has been in lockdown for thirty-five years. The village is located deep within a nuclear exclusion zone, and the guides are sweeping the ground ahead for radiation before we continue. Curious tourists peer out from behind the windows of the parked minibus, aware that no one has lived here since Chernobyl’s reactor went into meltdown in the early hours of April 26, 1986.

We’re only 16 miles north of the infamous Chernobyl Nuclear Power Plant, but this isn’t Ukraine. Dronki is in Belarus, where up to 70 percent of Chernobyl’s nuclear fallout fell when the wind started blowing north. Once home to over 20,000 people, some 800 square miles of irradiated land now form one of Europe’s largest wildernesses. It’s an accidental nature preserve where bison roam free in the shadows of Soviet statues, honey-making bees thrive in the forests and the rare Przewalski's horse gallops over former collective farmland.

“It’s safe,” our Geiger-counting guides call from the road ahead. As safe as an area that suffered extreme nuclear fallout just thirty-five years ago can really be, anyway.

“Chernobyl is very glamorous now,” Karina Sitnik says of the popular Ukrainian dark tourist destination over the border as we stroll down Dronki’s overgrown main road. “Especially Pripyat,” she adds. “It’s so touristy there. But you are one of the first to visit the Belarusian side.”

Read more: How to visit dark tourism destinations in an ethical way

It’s unusual to hear the site of the world’s worst nuclear disaster being called “glamorous,” but Ukraine’s exclusion zone became exactly that following the release of HBO’s wildly popular Chernobyl series - every influencer and media outlet wanted photos with Geiger counters in front of the iconic Ferris wheel.

In contrast to the stream of day tours on the Ukrainian side, Sitnik and her tour company Walk to Folk have only had permission to organise a select few tours into Belarus’ exclusion zone since late 2018 (Sitnik had only been allowed in around 10 times), when the Belarusian authorities opened the area up for low-level tourism. I was visiting in late 2019. A few months later, the pandemic once again closed the exclusion zone.

“Pripyat was a model Soviet town,” Sitnik continues as we carefully edge into the hallway of Dronki’s abandoned school, where a person-sized portrait of Lenin’s head greets us from the dusty corner. “But here in Belarus, these villages were all normal places to live.”

Dronki was home to 232 people before the disaster. The rural south of Belarus had none of the high rise apartment blocks, shopping complexes, and modern facilities that Pripyat did. But like Pripyat, Dronki was trapped in a Soviet-era timewarp when the inhabitants were unceremoniously evacuated from the fallout zone.

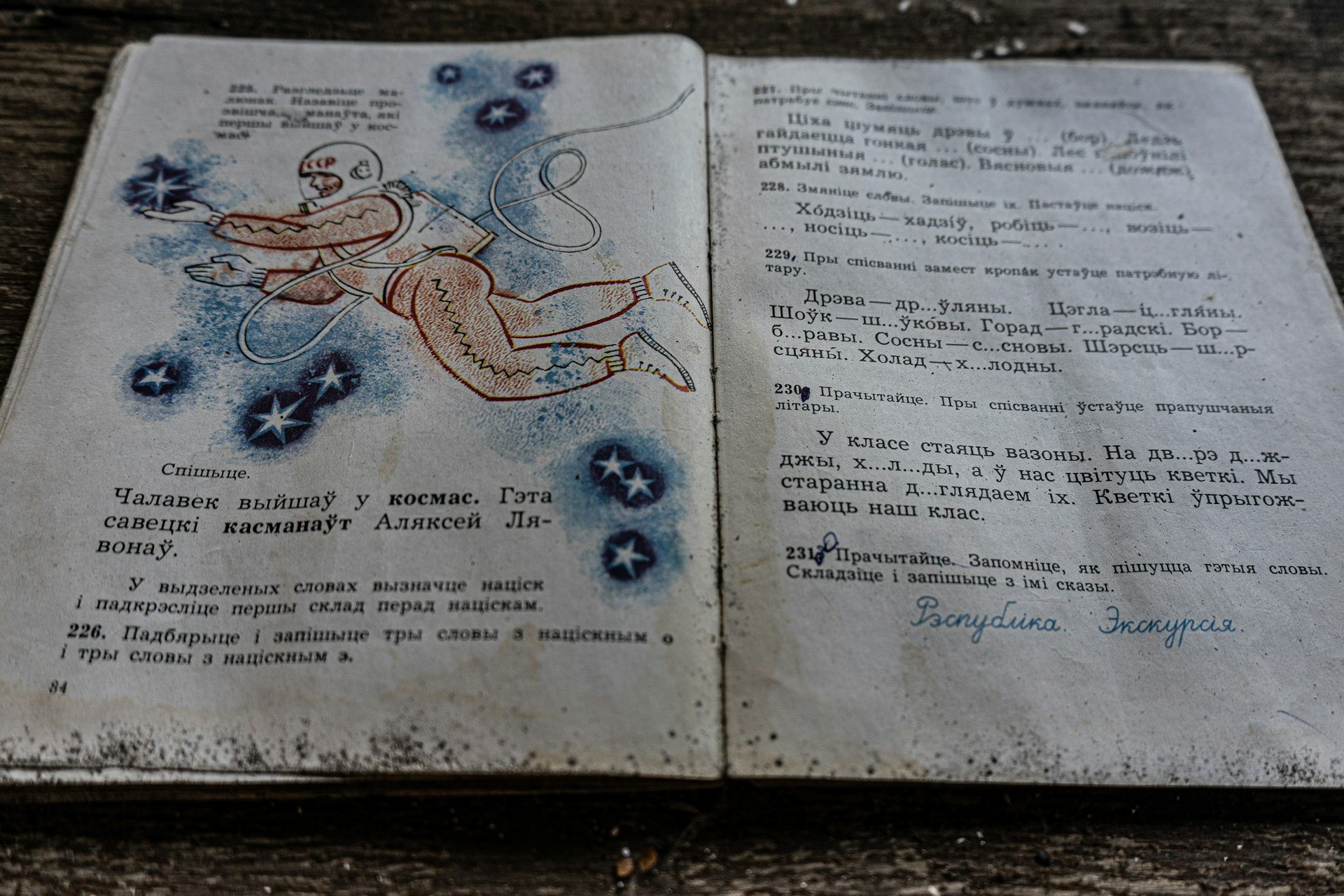

In the classroom, Sitnik spies fascinated dark tourists eyeing up maps of the Soviet Union, portraits and busts of communists leaders, newspapers dated to 1986 and books stamped with hammers and sickles. “Don’t take anything from the exclusion zone back home,” she warns the group. “No souvenirs, they can all be radioactive. It’s good for your health to leave them here."

The Soviet Union may have long ago disappeared, but the radiation hasn’t. Radiation levels are deemed ‘safe’ by the authorities, but only for brief visits. Older folk are allowed back once a year to visit cemeteries and war memorials, but no one has ever been allowed to permanently return to Dronki or any of the other 95 abandoned villages in the exclusion zone.

Along the Pripyat River, we see barges and boats rusting on the banks. The next village we visit is surrounded by open farmland, and Pripyat and the Chernobyl Nuclear Powerplant can just about be seen on a clear day from the top of a 30-metre high fire watchtower.

“Pripyat is always busy," says Sitnik as she points out the city far off in the distance. “But you can visit Belarusian Chernobyl and be one of only twenty people and a few dogs!”

Belarusian Chernobyl is home to more than a few stray dogs, though. As we drive along a heavily wooded road, the driver slams the minibus to a halt.

“Bison,” says Sitnik. “Through those buildings!”

Through the broken windows of a derelict house are the unmistakable silhouettes of two bison; one large, one small. 16 rare European Bison were introduced to the exclusion zone in 1996; now there are 145.

“The exclusion zone is one large wildlife sanctuary,” says Sitnik. Officially titled the Polesie State Radioecological Reserve, this off-limits area has unintentionally evolved into Belarus’s largest nature reserve. As well as the bison, official figures name 1251 species of plants, 54 mammals (including wolves, wild dogs and the endangered Przewalski's horse) and 280 species of birds.

Our last stop before decontamination is the exclusion zone’s research centre. We’re shown around by a radiochemist in military fatigues, with Sitnik translating. 700 people are employed in the zone studying the effects of radiation on the ecology, carrying out conservation projects and working on economic pursuits such as logging (sustainable logging, we are told). The most recent pursuit is beekeeping. Bees seem to thrive in the zone, and the radiochemist’s latest job is testing honey for radiation.

There are plans to build accommodation for brave (or perhaps foolish?) tourists who want to spend the night in the exclusion zone. The tourism focus isn’t necessarily dark tourism, though, as it is in Ukraine’s Chernobyl, but wildlife tourism.

The tour ends at a checkpoint on the outskirts of the exclusion zone. Before we’re allowed to leave the minibus is decontaminated with pressure hoses and the tourists pass through human-sized Geiger counters. My shoes are scrubbed, and my feet are given one last Geiger counter test to catch any sneaky plutonium isotopes trying to escape the exclusion zone.

Sitnik wants more people to see not only the wildlife within the exclusion zone but the lasting effect that the Chernobyl disaster has had on Belarus. Tourism is in the early stages here, and Sitnik’s biggest fear is that the exclusion zone will be opened to trophy hunting - it’s obviously not the sort of tourism she envisions for her country.

“The bison aren’t supposed to be hunted,” says Sitnik apprehensively as we pass through the last checkpoint and begin the journey back to Minsk, the Belarusian capital. “But this is Belarus.”

You might also like:

Chernobyl is seeking Unesco World Heritage status

Chernobyl’s Reactor No. 4 control room is open to the public for the first time

![Photo/File #: 12MP ..Country: Great Britain..Site: Hurst Castle..Caption: 12MP aerial..Image Date: [November 2021?]..Photographer: ExploringWithin MUST CREDIT..Provenance: Watch 2022](https://lp-cms-production.imgix.net/2022-03/GBR%20Hurst%20Castle%20MUST%20CREDIT.JPG?auto=format&w=140&h=140&fit=crop&q=75)