The fabled silver mining cities of central Mexico are a great place to dig into some significant (if not always so glittery) periods of Mexican history.

We’re not just talking about the regions’ former mineral wealth (though to this day minerals are still extracted from some working mines), but the architectural and other riches of the northern central highland’s main mining towns, Zacatecas, Guanajuato and San Luis Potosí. The grand, faded, colonial buildings that fill these towns are the indirect legacies of indigenous slave laborers who worked under horrific conditions to extract vast quantities of silver (along with gold, copper, lead and iron) for greedy prospectors and fabulously wealthy barons.

Zoning in on Zacatecas

It all began, so the story goes, in the mid-1500s when a local Chichimec man gave a piece of silver to a Spanish conquistador. Soon, mining operations were digging up ton after ton of the precious metal and transporting it to Mexico City for the Spanish crown. By the 18th century Zacatecas was producing 20% of the silver of Nueva España (New Spain, as central Mexico was then known). At the same time the town became an important base for Catholic missionaries whose main legacy is the imposing cathedral, a dominating, baroque, pink-stoned building that leaves no doubt of the influence of the church at the time.

Today Zacatecas’ streets are still lined with handsome colonial buildings. The massive 18th-century Palacio de Gobierno (Government Palace), stunning 19th-century theatre, Teatro Calderón, former Jesuit colleges and numerous churches are all worth a look, but the city’s highlight is Museo Rafael Coronel. This converted 16-century convent on the northern end of town houses Mexican folk art and a selection of 5000 traditional masks collected by a local artist, Rafael Coronel (who happened to be the son-in-law of artist Diego Rivera). To get a sense of the less opulent life of the miners whose work paid for all these architectural gems, visit Mina El Edén. A working pit from the sixteenth century up until the 1960s, it now offers a sanitized but still interesting insight into the conditions underground. For a more lifting experience, zip across on the teleférico (cable car) to Cerro de la Bufa (so called because the hill’s shape resembles una bufa, a Basque wineskin), which affords vistas across the valley in which Zacatecas lies.

If all that sightseeing makes you thirsty you can prop up the bar at Cantina 15 Letras, an atmospheric drinking spot whose walls are lined with photos of old Zacatecas. Or, for a fine-dining experience, head to Restaurant La Plaza in Hotel Quinta Real, an elegant spot overlooking a bullring and historic aqueduct.

Glistening Guanajuato

If any town represents Mexico’s Age of Silver, it’s Guanajuato. Around 1558 one of the richest silver veins ever found was uncovered in the area around what became the city, and in over two centuries Guanajuato had become the world’s leading silver producer. One of the wealthiest mines, La Valenciana, was originally tapped in the 1700s and has recently been reopened by a Canadian mining company.

To get a sense of a miner’s harsh workplace of the time, head north of the city center to Bocamina de San Cayetano or neighboring Bocamina de San Ramón where you can don a hard hat and enter one of the tunnels. There’s also the chance to talk to miners who worked these pits more recently. Close to the mines looms the incredible Templo La Valenciana (completed 1788 in the Churrigueresque style) with its massive ornate golden interior. Various legends surround its construction: one says that the owner of San Cayetano mine built it to honor the eponymous saint after striking it rich; another says that it was a silver baron’s atonement for having exploited his miners.

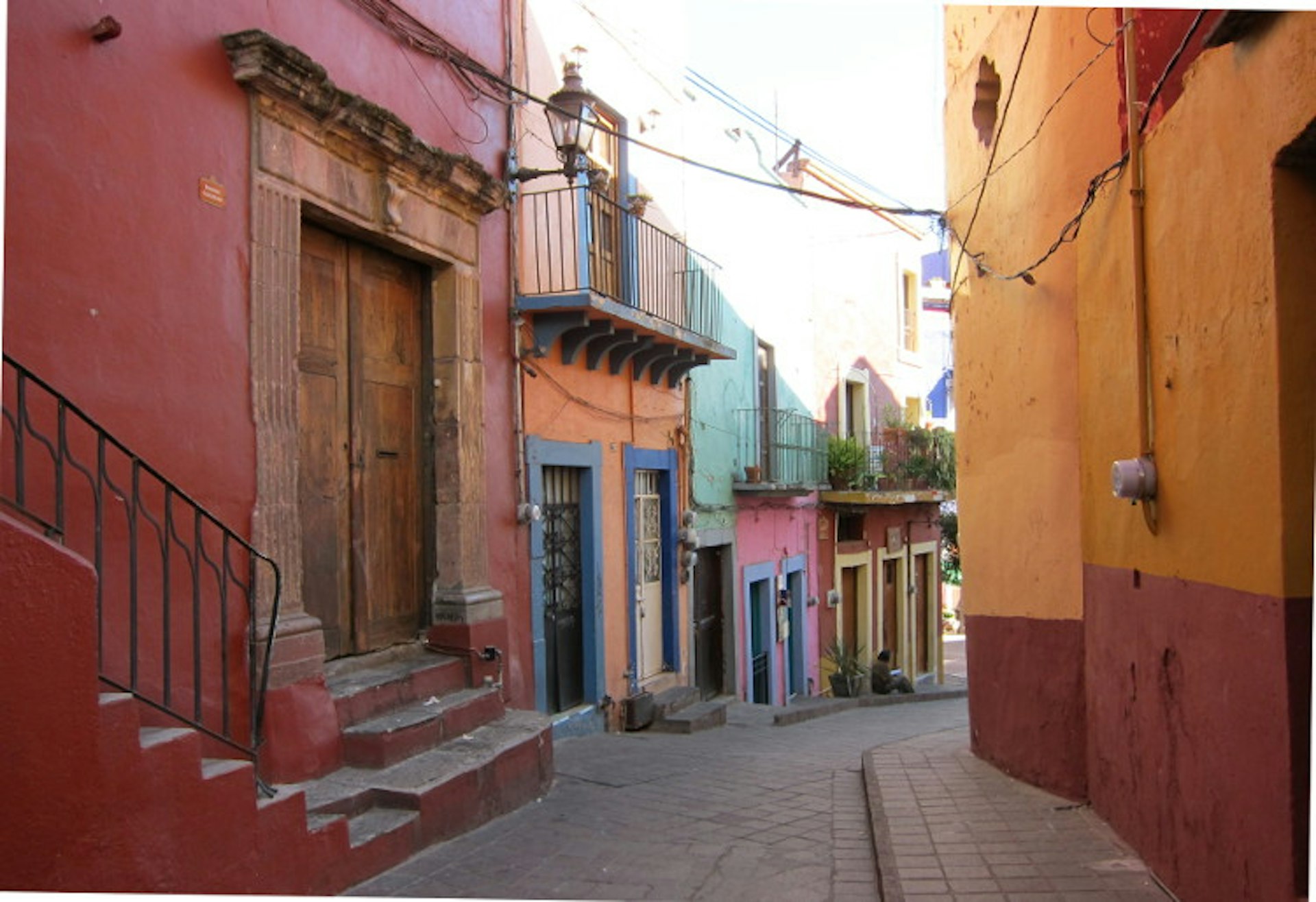

In the center of Guanajuato, opulent colonial buildings line two central streets, while beyond the main boulevards a series of pale pinks, blues, greens and purples cascade down the mountainside like a frozen kaleidoscopic image. The city is the seat of an eponymous university (whose incongruous 1950s university building and ramparts controversially dominate views of town), meaning there are plenty of culture and entertainment options. Take in a performance at Teatro Juárez, a theatre festooned with statues and columns and lavish interiors, visit Museo de Diego Rivera, the birthplace of the famous artist, and explore the Alhóndiga, a granary-cum-museum which was the site of the first battle in the war for Mexican independence.

Aside from museums, part of the joy of Guanajuato is simply taking a stroll through its small plazas – Baratillo, Jardín de la Union, de la Paz and San Fernando – which lead in a natural down-the-valley progression, but the very best way to explore the town and polish up your Spanish is at a nightly street party. Known as callejoneadas, these parties involve a group of musicians and singers leading you through the hilly streets and callejones (alleyways) as they sing songs and tell stories.

For a more sobering experience, head to the Museo de las Momias and its displays of the mummified remains of bodies removed from graves at the turn of the 20th century after relatives defaulted on paying an obligatory interment tax. Though macabre, the museum provides an insight into the Mexican preoccupation with and open attitude towards death.

And if that hasn’t dampened your appetite, don’t miss the local cuisine on offer at the food stalls beside the Mercado Hidalgo, an incongruous building that resembles a French train station (Mexican dictator Porfirio Díaz, who commissioned the market, was a staunch Francophile), or, for something more substantial, seek out Casa Valadéz. This place not only has a ring-side seat on the main plaza, but serves delicious enchiladas mineras (miners’ enchiladas), a local take on a trusty enchilada, topped with potato, carrot and cheese.

Striking San Luis Potosí

Founded in 1592 and named, optimistically as it turned out, after an immensely rich silver town in Bolivia, San Luis Potosí never achieved the output levels of its South American counterpart, but did thrive as a ranching and commercial centre. In the 17th and 18th centuries it was an important centre for Jesuits, Augustinians and Franciscans whose orders constructed some of the city’s extraordinary churches. One, part of a former monastery, is now the Museo Regional Potosino and features a stunning gold and aqua private chapel.

The result of this rich history? These days, San Luis Potosí epitomizes colonial style. The city comprises parks and plazas lined with grand museums and linked by pedestrian alleys. Highlights here include the Museo Federico Silva, a 17th century building that has been given an extraordinary makeover and hosts exhibitions of contemporary sculpture; the Museo Regional Potosino, with fascinating displays on pre-Hispanic Mexico; and the Teatro de la Paz, a neoclassical theatre from the 19th century where the local symphony orchestra performs. San Luis Potosí is also a great place to buy artisan goods: check out La Casa del Artesano and Casa Grande Esencia Artesanal. Finish your day at Antojitos El Pozole with an enchilada potosina, a local take on a national favourite which is colored red thanks to its chili content.