In families like mine, the repercussions of the Great War have been sustained and devastating. In others, the involvement of family members in that epoch-defining conflict is seen in a more positive light. This year marks the centenary of the war’s outbreak and people from every corner of the globe are making pilgrimages to its major battlefields in order to commemorate the events that their family members and countrymen took part in.

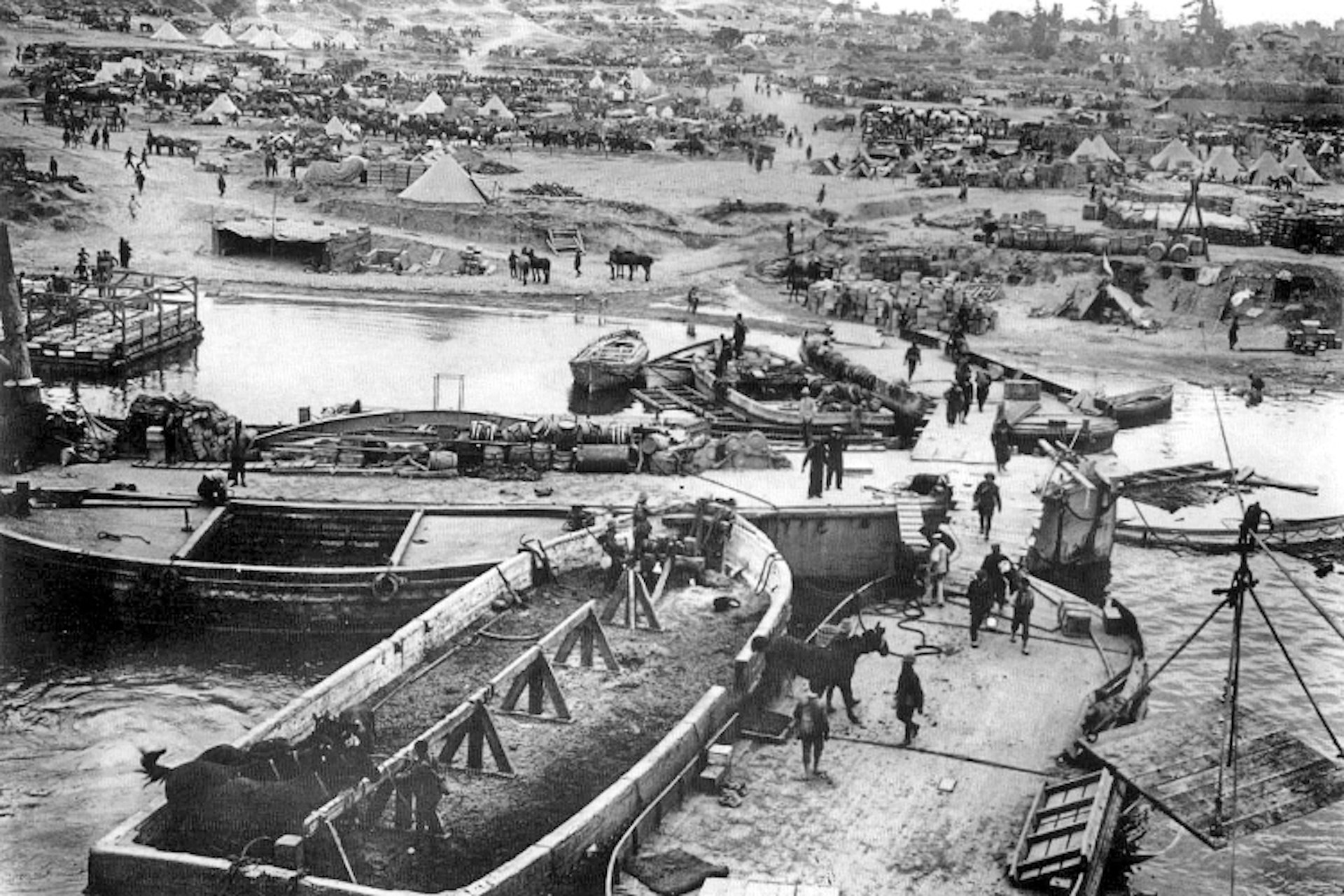

For Turks, Australians and New Zealanders, none of those battlefields are as sacred as the Gallipoli Peninsula in Turkey, where 130,000 men died during a during a bloody battle fought between April 1915 and January 1916.

My grandfathers’ Great War experiences

Both of my grandfathers signed up with the Australian Imperial Force early in the war and boarded troop ships heading to the other side of the world, excited about the travel, happy to be with their mates and convinced of the righteousness of the Allied cause. Strapping young farmers full of optimism, they returned from Europe different men entirely: gaunt, shell-shocked and traumatised. One drank to block out his memories, the other worked in the wheat fields from dawn to dusk so as to exhaust himself and then – hopefully – sleep the night through. He didn’t, though, and my father and his brothers were woken almost every night by my grandfather’s screaming nightmares. God knows what horrors he witnessed in the trenches.

Before she died, I asked my mother why she thought her father had become an alcoholic. Was it just about the war? ‘It’s complicated,’ she sighed. ‘He had a bad war and I think he came back half a man. Couldn’t give his wife the life that he thought she deserved, couldn’t earn enough to feed his children properly, couldn’t sleep at night. I don’t think he drank to block reality out. I think he drank to try and regain that feeling of being whole again. Of being a real man. And I think he lost that feeling in the war.’

Visiting Gallipoli for the first time

I thought about my grandfathers’ war experiences constantly when I first visited Gallipoli a decade ago. My partner, six-year-old son and I took a guided bus tour of the Northern Peninsula led by a former Turkish naval officer affectionately known as Captain Ali. Captain Ali worked for the Hassle Free Travel Agency and he really knew his military history. He was also great at explaining the events of 1915 to children. At one point I asked a question about the unsuccessful Allied naval attack on the Dardanelles in March 1915. My son turned to me and said loudly ‘Weren’t you listening, Mum? Captain Ali said that the Turkish navy knew that the English were coming and so sent a little boat out to put bombs in the water. They were cleverer than our side, not braver, and that’s why they won.’ Indeed.

‘ I am not ordering you to attack, I am ordering you to die.’

During one of my subsequent visits, I decided to do some exploring by foot rather than car. I walked through fields of crops and then up a steep slope through pine-scented forest to Chunuk Bair (Conk Bayırı in Turkish), the ridge where some of the most-fierce fighting of the campaign occurred. I rested next to the tranquil New Zealand Cemetery and Memorial and then wandered across to the Conkbayırı Atatürk Memorial, which commemorates the great man’s famous order to his 57th Infantry Regiment: ‘I am not ordering you to attack, I am ordering you to die. In the time it takes us to die, other troops and commanders will arrive to take our places’. The 57th held the line but was almost totally wiped out in the process. Such bravery is almost unimaginable, but was par for the course here at Gallipoli.

The day after my trek to Chunuk Bair I headed to Eceabat and bumped into a group of Australians who had spent the day trekking through the main area held by Anzac troops during the Gallipoli campaign. They had followed the Anzac Walk outlined on the Australian Government’s Department of Veterans’ Affairs ‘Gallipoli and the Anzacs’ website (https://anzacportal.dva.gov.au/), and had visited 14 historically important locations including Lone Pine and The Nek. One of them, the father of two boys, had been particularly moved at Lone Pine. ‘I saw the grave of a 14-year-old boy called James who died from enteritis. My oldest son is called James and spends most of his time playing X-Box. I can’t stop thinking about how I would feel if it was his name there on that grave.’

2015: The Centenary of the Landings

In Australia, many returned servicemen don their medals and their best suits once a year, on Anzac Day (25 April) and march in commemorative parades. Both of my grandfathers refused to do this, but allowed their children and grandchildren to wear their medals to special Anzac-related school assemblies instead. I desperately wanted to wear my paternal grandfather’s Military Medal – he was a hero, after all – but that honour went to my oldest cousin. My grandfather allowed him to wear it on one condition: that he never, ever consider signing up to the army.

I didn’t join the heavily subscribed ballot for a ticket to the dawn service at Gallipoli on 25 April 2015, so I won’t be at the commemorative site when the centenary of the Allied landings is marked at dawn. But I know that I will return again to walk the battlefields and pay tribute to the many men – Australian, British, New Zealand, French, Canadian, Indian and Turkish – who lost their lives on this now tranquil and beautiful peninsula on the far edge of Europe.

How to visit

- Crowded House Tours (http://www.crowdedhousegallipoli.com), a highly recommended outfit based in Eceabat, close to the battlefields.

- Hassle Free Travel Agency (http://www.anzachouse.com), still one of the most reputable companies offering battlefield tours on the peninsula.

- The Gallipoli Houses (http://www.thegallipolihouses.com), a boutique accommodation option located within the Gallipoli Historical National Park itself. Operated by military-history buff Eric Goossens and his wife Ozlem, this place is perfect for those who want to explore independently as Eric is a mine of information about the battlefields and can offer plenty of advice about walking and driving routes.

- Kenan Çelik (http://www.kcelik.com), one of Turkey’s foremost experts on the Gallipoli campaigns, organises customized full-day tours.

Virginia Maxwell researched Gallipoli for the upcoming edition of Lonely Planet’s Turkey guidebook, to be published in 2015. Follow her at instagram.com/maxwellvirginia. Lonely Planet contributors do not accept freebies in return for positive coverage.